The Historical Stories of Cynthia Harnett

Style: Good

Attitude: Positive → Edifying

In Brief: Gentle, readable and edifying historical stories featuring youngsters in homely situations between the 15th and 17th centuries.

Age Range: Pre Teens+

Period: 15th C

Genres: Historical

Notes:

Between 1949 and 1971 Cynthia Harnett wrote and illustrated six historical novels for children. The first in order of writing, The Great House, was in fact the last in order of setting, taking place in the late 17th century during Christopher Wren’s lifetime. The second to be written, The Wool-Pack, is set in the Cotswolds in 1493 and won the Carnegie Medal when it was published in 1951. The others, in no particular order, span the years between the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 (Ring Out Bow Bells!) and 1554 when the Princess Elizabeth was imprisoned at Woodstock during the reign of her sister Mary Tudor (Stars of Fortune). There’s little attempt at continuity: none of the principal characters appears in more than one story and only a handful of the supporting cast. (William Caxton, for example, is an apprentice in The Writing on the Hearth in 1439 and by 1482 is a successful mercer and pioneer of printing in The Load of Unicorn). Slightly oddly, some of the books changed title as they crossed the Atlantic. “The Load of Unicorn” is named “The Cargo of the Maddalena” while “Ring Out Bow Bells!” Becomes “At the Sign of the Green Falcon”.

During her lifetime, Harnett’s books were tremendously popular with schools and libraries. They were published at a time when juvenile historical fiction was undergoing a resurgence in popularity and a change of style. Rosemary Sutcliff, Henry Treece, Geoffrey Trease, Ronald Welch and other mid-20th-century authors were producing books which portrayed moments and movements of history in a fresh style and often with young point-of-view characters. In contrast to these other authors, whose characters were often in the thick of war and politics, Cynthia Harnett wove her stories around semi-rural homes and families with the great movements of the world merely a backdrop to the more local action.

There is a gently didactic feel to all the stories. No opportunity goes by without some aspect of late-mediaeval life being explained: the construction of hose on a wooden cross; the way of life in the University of Oxford; the tenets of heraldry; the need for a head of water when running a water-mill; the trend towards pasturing sheep in the rich grass of the Cotswolds. A postscript to each volume details the real history behind the fictional story: which buildings are still in existence, which were real once, and which were invented; which people were real and which incidents were based on documentary evidence. The books might be discounted as How-We-Used-To-Live schoolbooks disguised as stories. But in fact the vivid characters, the charming illustrations, and the storylines themselves, however lightweight, ensure that the books are enjoyable in their own right.

The 1980s brought grittier, contemporary, city-based fiction to young people. The gentler and more educational historicals fell out of publication and popularity with perhaps a few exceptions such as Sutcliff’s iconic Eagle of the Ninth Trilogy. These days, however, there’s a movement towards “Modern Classic” imprints by mainstream publishers as well as cottage-industry publishers focusing on smaller markets. The former are keen to give a sense of continuity and solidity to their brand while digital printing and large online marketplaces such as Amazon have made the latter viable. In addition, of course, online resellers for secondhand books make it easier than ever to pick up the fallout from the county and school library clearouts of the 80s and 90s.

Historical stories for youngsters from the decades immediately following the War share two key characteristics: a sense of a history worth knowing in between the lines of the story; and patterns of words and actions which portray the mindset and speech of its period without alienating the modern-day reader. The words and sentences in all of these stories are intelligible to children but the way of speaking is satisfyingly different, reflecting for the most part the courtesy, graciousness and attitudes of respect of another age. In contrast, many modern historicals are populated by essentially 21st-century characters, either by virtue of some sort of time-travel plot device or because the characters, while presented as historical, actually represent this century’s outlook for all that they’re inhabiting another century’s costume.

There are wider questions around this same issue. To what extent do the characters portrayed by Harnett and her contemporaries simply reflect their own author’s mid 20th-century milieu? How much should an author be allowed to smooth off the rough edges of her characters’ behaviour in the name of making things easier for young readers? Should edification carry more weight than strict realism? I hope to explore these in a separate article.

While other authors, perhaps, were more interested in miltary and political history, Cynthia Harnett was fascinated by social history and that at the micro level. A trained artist, she was able to illustrate her own stories and did so for the most part by highlighting tiny homely details from the narrative, going so far as to point them out to the reader in the postscript she wrote for each book. In some cases she’s drawing an item which is on display in a local museum or which can be seen in a painting of the period. In other cases she’s combining a contemporary description with something similar she’d seen herself.

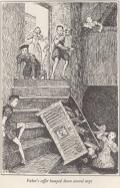

The illustrations are full of activity, sometimes depicting a specific scene from the story, sometimes a general picture of the people or places being described, sometimes simply an object which is mentioned nearby in the narrative. In every case there’s a delightful combination of simplicity of line and liveliness of action. People are always right in the middle of something: pulling a tooth, dancing a round, saddling a horse, or pointing the way. Everyday items are shown as though they were in use and not merely exhibits in the museum where the author probably encountered them.

The frontispiece of Stars of Fortune, for example, illustrates the scene where the Washington & Spencer children, playing King of the Castle, tumble Father’s chest downstairs so that it bursts open. The chest is shown mid-tumble, the boys left on their hands and knees as it slips from their grasp, the girls looking on aghast and peeping around doors or hanging over the stair-rail to watch. Elsewhere in the same book, a small insert shows a 15th-century pressure cooker which provides a slight moment of comic relief in the story. Even this inanimate object is brought to life, captured just as the steam is escaping from the valve. With the exception of The Writing on the Hearth, illustrated by Gareth Floyd, the same is true in the others books: every picture is full of life and the clear affection the author had for the characters she’d created.

Indeed a sense of lively affection is a notable feature of Cynthia Harnett’s stories: most often shown in the quiet bustle of family life and the respectful affection of the children for their parents. Her families are mostly what might be termed upper middle-class: well-to-do landowners, architects with reasonable patronage, merchants or mercers in good standing with their respective Guilds, the owners of small but profitable businesses. They tend to be located outside the main cities (although that could well include areas which are now within what we think of as London) and are a step or so removed from the great currents of court & politics. It’s the gentle currents of family life and the small crises of home and district which mostly provide the tension in these stories: a lost mortgage deed, a dishonest fleece-packer, a marriage alliance between two local families, fights between two sets of apprentices.

That’s not to say, though, that the people and places of the wider world have no effect on the characters or are not introduced into the story. Rather, they form a backdrop, sometimes explained as the causes for the actions or attitudes of characters. Stars of Fortune, for example, turns on the imprisonment of Princess Elizabeth during the reign of Mary Tudor; Ring Out Bow Bells is set in the aftermath of Agincourt; in The Great House, the children’s father is a friend of Christopher Wren and Geoffrey wants to follow in his footsteps; Master Fetterlock in The Wool-Pack explains to his son about the working of the Wool Staple which controls the export of any English wool; and so on. Explanations of what are historical facts to a modern-day reader are discussed as matters of current concern between the characters.

Any youngster reading the stories nowadays will be struck by the obedience and respect demanded of their young counterparts in these books. Adult authority is rarely challenged or if it is then the resulting punishment – usually physical – is expected and accepted. The children of the 1950s and 60s, the original readers of Harnett’s stories, would have been at least more familiar with such an idea of parental authority, although it would not have been so absolute even then. Today most such attitudes are alien to youngsters and adults alike. That’s not to say that the adults in the books are cruel or spiteful. In fact they’re fairly indulgent, finding one excuse or another not to punish their children in spite of bad behaviour. Young Cecily Bradshaw, to whom Nicholas is engaged in The Wool-Pack, knows her father won’t forbid her the fair as he first threatened but will whip her instead. But when Nicholas offers to take her punishment upon himself Master Bradshaw in good humour remits even that punishment.

Cecily is a fair example of a Cynthia Harnett girl character. She’s determined, artful, demurely respectful when occasion demands, but not afraid to take a risk to get what she wants or to help a friend. We first meet her up a tree where she’s hidden to see her husband-to-be go past. Although she admits that she’d normally be wearing her brother’s clothes to climb trees she’s no tomboy. Steven Greydanus, surveying films over at decentfilms.com, takes issue with the “Lament of the Corset” (in http://www.decentfilms.com/reviews/aliceinwonderland2010 for example). Well, here at goodtoread.org my pet peeve is the Girl Dressed As A Boy Syndrome where Historical Girl can’t possibly do anything of note because she is Not A Boy. However, this author is having none of that. Her girls are girls of their time, learning housewifely tasks and not expected to carry out the same roles as their brothers. But they’re also independent-minded, resourceful, confident, caring and eager to learn. And their adult counterparts are their own women, able to cope by themselves while offering motherly wisdom and comfort and intervening where necessary to forestall paternal wrath. For a striking woman of an older generation, look out for the formidable Great-Aunt Bath in Stars of Fortune, Matriarch of her clan, and ready to take on anyone in a battle of words.

The children of Harnett’s stories are rarely left in doubt as to the moral import — and consequences – of their actions. Laurence Washington is nothing but forthright when he discovers that his sons have been drawn into a group secretly visiting the imprisoned Princess Elizabeth: he makes it clear that not only their only liberty and lives would be in jeopardy if they were discovered but also those of their family and friends. In a turning-point scene in The Load of Unicorn, Bendy loses his temper with his brothers’ apprentice Humphrey when he finds him rummaging through Bendy’s own things in the loft they share. He hits out at Humphrey, inadvertently causing him to tumble down a loft ladder. Bendy’s father is sent for and arrives aghast at the thought that his son might have killed someone through his hotheadedness. Although as it turns out Humphrey is merely bruised, John Goodrich makes it clear to his son what the consequences might have been and tells him plainly that, although he had been provoked, he had let his temper get the better of him more than once. Bendy, to his credit, not only accepts this but also starts to see beyond his own immediate needs and recognises that his father also is in a difficult position with respect to his sons, Bendy’s older brothers. Finally, Master Goodrich advises his youngest son to examine himself carefully over the matter of his temper before going to Confession.

This commonplace acceptance of day-to-day religion is especially noteworthy nowadays when references to religion in contemporary or historical stories tend to be peripheral at best, scandalous at worst. What the author’s own faith and beliefs were is an open question. She was almost certainly Christian, and she’s known to have spent her final years in a Catholic nursing home, which makes it plausible, although by no means certain, that she was indeed Catholic. Whatever her own beliefs were, she certainly has a respect for and an understanding of the beliefs of her characters. With the exception of her first book whose characters are of Quaker origins and where religion hardly plays a part, all her families have an active piety and a commonplace faith: lighting devotional candles for family members; going to confess before attending a dawn Mass; paying to have a church built or contributing to church furnishings and so on.

Authors & publishers continue to produce historical novels for children. Some, such as Gideon the Cutpurse or King of Shadows fall into the time-travel category, offering a view of an historical period through modern eyes. Others take place in a parallel universe where recognisable history has taken a slightly different turn: Larklight, for example, or the Stravaganza series. Still others are simply historicals such as Peter Raven Under Fire or a mixture like Victory. Each of those mentioned above is enjoyable and, within its own world, authentic. But it’s rare to find a book which manages to capture such a gentle picture of everyday life in an historical period as the six historical stories written by Cynthia Harnett.

Friday 4th November 2011